Lab Now Includes IHT Heart Rate Technology to Motivate Students to Increase Fitness Levels

A 2017 Johns Hopkins University study motivated Mableton Elementary School (Cobb County, Ga.) teacher Sean Splawski to ensure his students stayed ahead of a troubling societal trend toward inactivity. Powered by IHT heart rate technology, Splawski’s Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics (STEAM) Lab students focus the relationship between exercise at an elevated heart rate and physical and emotional wellness as key components of a healthy lifestyle.

“I read a 2017 article that focused on the largest study done where people who ranged in age from 6-80 wore heart rate monitors for a certain length of time,” Splawski said. “The major finding shocked me. It showed that a 19-year-old is [only] as active as [an average] 60-year-old. I thought right then that we needed [as a society] to do something about that.”

The study determined that between 50 and 75-percent of participating adolescents between ages 12-19 did not meet the World Health Organization standard of at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity every day. Their activity levels lined up more consistently with adults older than 60, for whom the WHO recommends 75 minutes of MVPA per week.

Splawski partnered with his campus physical education leader to determine how Mableton’s students would gain active time in the day without sacrificing learning time. They applied for – and won – a $12,000 grant that they used to purchase exercise equipment including the IHT ZONE wrist heart rate monitors for students to use.

“We bought equipment that we use outside with the kids and keep them engaged with a movement-based curriculum,” he said.

Splawski wants students to spend at least 20 minutes during each class exercising at an elevated heart rate. The combination of the state goal and heart rate technology that shows students if they are on track to meet the goal has proven very effective.

“The students are really energized when they wear them,” he said. “When they see their heart rate, they really want to achieve the goal.”

Splawski does not teach in the PE world, where getting students active remains the top priority. But he sees the value of physical activity, and he uses his IHT ZONE inventory at every opportunity. He developed a curriculum around active learning — Eduscize — and shared it with academic colleagues.

“Fitness is a way of life,” Splawski said. “I’m not a health and PE teacher. I focus on early childhood education, and this is one of the most important things I do.”

Making Physical Activity a Regular Part of Classroom Learning

Splawski makes fitness a priority in his classes for several reasons:

- To combat the trend that today’s youth are less active than ever by modeling what he considers proper lifestyle habits; and

- To teach students that physical fitness can help them navigate emotional issues

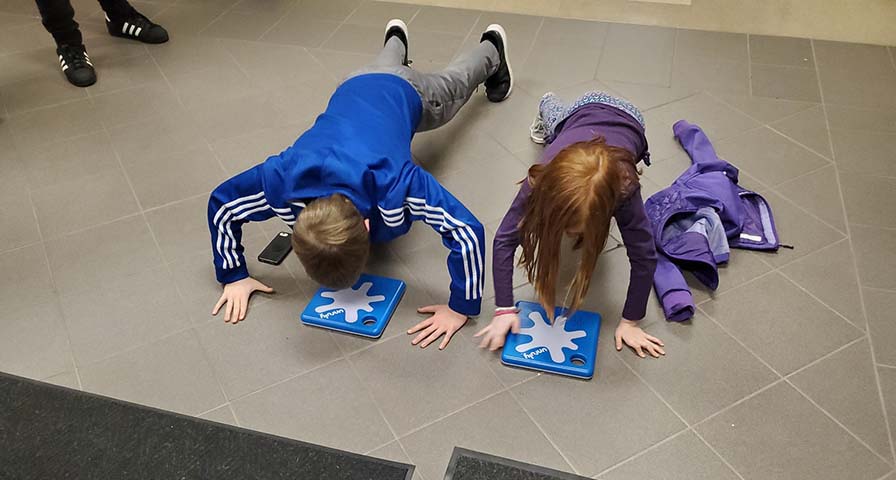

Each day, Splawski welcomes his students with a classroom designed for activity. Students pick up their ZONE monitors, go over the day’s goals and get moving. Some days Splawski takes students into the cafeteria or hallway for a modified version of circuit training. Other days, students stay in his lab but remain active – moving around the room or in place – to maximize their engagement and focus on the lesson.

Each day, Splawski welcomes his students with a classroom designed for activity. Students pick up their ZONE monitors, go over the day’s goals and get moving. Some days Splawski takes students into the cafeteria or hallway for a modified version of circuit training. Other days, students stay in his lab but remain active – moving around the room or in place – to maximize their engagement and focus on the lesson.

“From a sciences standpoint, we research health issues,” he said as an example. “I have students find articles that they can understand. What will happen to you if you over-eat? If they can find just a paragraph or two that explains it, that’s good enough to start with. Then we get them moving.”

He often has students research how much exercise they need to get to overcome a bad food choice as Takis or Cheetos instead of an apple.

“They have to look it up,” he said. “If they eat 13 Takis, it takes 16 minutes of running to burn that off. We play games and do things that are supposed to compare [model behavior] to the things that they are doing.”

The heart rate monitors work with all of Splawski’s lessons. Even the robots Splawski’s students use to learn coding and programming skills get active.

“With our robotics group we’ll do coding while we’re wearing the monitors,” he said. “I’ll see who can program a robot to move quickly and then see if the students can race the robots.”

Splawski’s movement-based curriculum enables him to teach students behaviors they should be modeling in a world where activity continues to dwindle. They need to see healthy habits somewhere if they aren’t seeing it at home or with friends.

“Parents and peers are very much influencers, good or bad,” Splawski explains. “If students see their parents or friends behaving in certain ways, they are going to copy that behavior. If parents aren’t active, then there is a good chance that the child isn’t active either.”

“Parents and peers are very much influencers, good or bad,” Splawski explains. “If students see their parents or friends behaving in certain ways, they are going to copy that behavior. If parents aren’t active, then there is a good chance that the child isn’t active either.”

Splawski doesn’t confine his teaching to just his students. He’s trying to get more colleagues to see the importance of movement in the classroom. Teachers, he said, must adapt their strategies because student use of technology has eaten into the time students used to spend moving.

“Society is on a bad path and we have to do what we can to fix that,” he said. “If you think about a child’s day, the average kid still looks at a screen for seven or nine hours [for each 24 hours]. At school, 65 percent of their time [4 and a half hours] is spent in a seated position. Schools need to understand that and need to create more opportunities for movement.”

Teaching Students to Manage Their Emotional Wellness Through Activity

His students’ overall health, both physical and emotional, drives Splawski’s ever-changing STEAM Lab curriculum. Citing data that shows today’s children spend less time exercising than ever before, Splawski uses heart rate – and specifically time spent exercising at an elevated heart rate – to help his students relate physical fitness to emotional fitness.

Using the ZONE monitors to encourage students to become active ties directly to mental health because physical activity can impact body image. A recent survey of his students showed him how essential those lessons are.

“We talk about body image,” Splawski said. “That’s a major issue for kids. We did an exercise one day where we asked students to take a selfie and only half the class wanted to. That’s because somewhere they have learned to not like their body, and that’s part of the pressure they find with social media.”

Most social media apps are designed for teenagers, but Splawski knows he won’t convince his young students to stop using the apps. Instead, he teaches them how they can improve their self-image through exercise, giving them something positive to focus on.

“We’re trying to create a positive-growth mindset,” Splawski said. “We want the students to be confident about themselves. We focus on how the monitors can help change your body image through exercise.

“Even if it’s just taking a walk, we really just need them to understand how important exercise is,” he said. “If you can motivate one student to start exercising…if we can get one kid modeling that type of behavior, every other kid will see it and we’ll begin changing for the good.”